DeltaNet Explained (Part I)

A gentle and comprehensive introduction to the DeltaNet

This blog post series accompanies our NeurIPS ‘24 paper - Parallelizing Linear Transformers with the Delta Rule over Sequence Length (w/ Bailin Wang, Yu Zhang, Yikang Shen and Yoon Kim). You can find the implementation here and the presentation slides here.

Linear attention as RNN

Notations: we use CAPITAL BOLD letters to represent matrices, lowercase bold letters to represent vectors, and regular lowercase letters to represent scalars.

What is linear attention?

The vanilla softmax attention mechanism, though powerful, suffers from quadratic complexity in sequence length. Let’s see how linear attention addresses this issue by starting with the standard softmax attention (assuming single head):

\[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{Parallel\ training:} &&& \mathbf{O} = \mathrm{softmax}(\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^\top \odot \mathbf{M})\mathbf{V} &&\in \mathbb{R}^{L\times d} \\ \mathrm{Iterative\ inference:} &&&\mathbf{o_t} = \sum_{j=1}^t \frac{\exp(\mathbf{q}_t^\top \mathbf{k}_j)}{\sum_{l=1}^t\exp(\mathbf{q}^\top_t \mathbf{k}_l)}\mathbf{v}_j &&\in \mathbb{R}^d \end{aligned}\]Here,

-

\(L\) represents sequence length

-

\(d\) represents head dimension

-

\(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}, \mathbf{O} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times d}\) represent the query, key, value, and output matrices respectively.

-

\(\mathbf{M} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times L}\) is the causal mask for autoregressive modeling by ensuring each position can only attend to previous positions.

What linear attention

While removing softmax alone doesn’t immediately reduce computational complexity, it enables a crucial mathematical property: linearity. This property, particularly associativity, allows us to restructure the computations in ways that significantly improve efficiency. For training, researchers have developed chunkwise parallel techniques

For inference, we can also rearrange the computation as follows:

\(\begin{aligned} &&&&\mathbf{o_t} = \sum_{j=1}^t \mathbf{v}_j(\mathbf{k}_j^\top \mathbf{q}_t) &&&&& \mathbf{k}_j^\top \mathbf{q}_t = \mathbf{q}_t^\top \mathbf{k}_j \in \mathbb{R}\\ &&&&= (\sum_{j=1}^t\mathbf{v}_j\mathbf{k}_j^\top)\mathbf{q}_t &&&&&\text{By associativity} \end{aligned}\) $$

Let’s define a state matrix \(\mathbf{S}_t = \sum_{j=1}^t\mathbf{v}_j\mathbf{k}_j^\top\). Then the computation can be expressed as:

\[\mathbf{S}_t = \mathbf{S}_{t-1} + \mathbf{v}_t\mathbf{k}_t^\top \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times d}, \quad \mathbf{o}_t = \mathbf{S}_t \mathbf{q}_t \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\]This formulation reveals that linear attention is essentially a linear RNN with a matrix-valued state \(\mathbf{S}\) that accumulates key-value outer products, enabling efficient state (size) expansion from \(\mathcal{O}(d)\) to \(\mathcal{O}(d^2)\).

Why do we want state expansion?

Traditionally, RNN's hidden dimension is often the same (or of the same magnitude) as the input dimension, due to the expensive matrix-multiply-based state update. However, RNN solely relies on the recurrent state to remember the entire history and state size tends to be the bottleneck to remember sufficient amount of information, especially in retrieval tasks. We've been observing a substantial amount of research investigating hardware-efficient state expansion since Mamba1With this approach, we only need to store and update \(\mathbf{S}_t\) instead of maintaining all previous key-value pairs. This optimization dramatically improves efficiency: the time complexity for autoregressive inference reduces from \(\mathcal{O}(L^2d)\) to \(\mathcal{O}(Ld^2)\), while the space complexity improves from \(\mathcal{O}(Ld)\) to \(\mathcal{O}(d^2)\). These improvements make this method particularly advantageous in two scenarios:

-

Long sequence modeling where quadratic complexity of softmax attention could be a significant bottleneck.

-

During generation, where computation is usually memory-bound, removing the KV cache can significantly enhance inference latency for \(L \gg d\).

No Free Lunch: Key Limitations of Linear Attention

Unfortunately, there is no free lunch. The fixed-size state matrix in linear attention means it cannot perfectly preserve all historical information, making exact retrieval particularly challenging.

More formally, linear attention implements a key-value associative memory, which is the sum of outer products between keys and values \(\mathbf{S} = \sum \mathbf{v}_i\mathbf{k}_i^\top\). Assuming all keys are normalized to unit length, when we try to retrieve a value associated with a specific key \(k_j\), we get:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{S}\mathbf{k}_j &= \sum \mathbf{v}_i (\mathbf{k}_i^\top \mathbf{k}_j) \\ &= \mathbf{v}_j + \underbrace{\sum_{i\neq j} (\mathbf{k}_i^\top \mathbf{k}_j)\mathbf{v}_i}_{\text{retrieval error}} \end{aligned}\]To minimize the retrieval error term, we need \(\mathbf{k}_i^\top \mathbf{k}_j = 0\) for all \(i\neq j\) - in other words, all keys should be orthogonal to each other. However, this reveals a fundamental limitation: in a \(d\)-dimensional space, you can only have at most \(d\) orthogonal vectors. This explains why increasing head dimension helps (For example, Sun et al.

This theoretical limitation manifests in practice: vanilla linear attention has underperformed compared to softmax attention (by a large margin) in language modeling. The primary cause is memory “overload”: in this key-value associative memory system, we can only add new key-value associations without the ability to erase existing information. As sequences grow longer, this leads to accumulating “retrieval errors” that degrade performance. Indeed, as noted by David Eagleman in his book “Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain”,

“The enemy of memory is not time; it’s other memories.”

(Thanks to Kazuki Irie for the reference!). Recent advances in gated variants of linear attention (such as GLA

Click here to learn more about gated variants of linear attention

Given the close relationship between linear attention and RNN, it is no wonder that researchers want to enhance linear attention with the (forgetting) gating mechanisms, which has been shown unreasonably effective in nonlinear RNN

\[\mathbf{S}_t = \mathbf{G}_t \odot \mathbf{S}_{t-1} + \mathbf{v}_t\mathbf{k}_t^\top\]

with different structured parameterization for \(\mathbf{G}_t \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times d}\) for parameter efficiency, often with outer product structure. Different models have proposed various ways to structure this gating matrix:

For Decaying Fast weight

For GLA

For Mamba1

For Mamba2

Cf. Table 1 of GLA

DeltaNet: Linear Attention with Delta Rule

What is Delta Rule?

The Delta Rule

To understand this intuitively, imagine teaching a child to aim at a target. If they shoot too far to the left, you’d tell them to adjust right; too far right, adjust left. The size of the adjustment depends on how far they missed - a concept directly reflected in the Delta Rule.

Click to expand Delta Rule code

import numpy as np

def delta_rule(x, y, epochs=100, lr=0.1):

"""

Simple delta rule implementation

x: input features (N samples by D features)

y: target values (N samples)

"""

# Initialize weights

w = np.zeros(x.shape[1])

# Train

for _ in range(epochs):

for i in range(len(x)):

# Forward pass

pred = np.dot(x[i], w)

# Compute error

error = y[i] - pred

# Update weights

w += lr * error * x[i]

return w

# Example usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Generate toy data

x = np.random.randn(100, 3) # 100 samples, 3 features

true_w = np.array([0.5, -0.2, 0.1])

y = np.dot(x, true_w) + 0.1 * np.random.randn(100)

# Train

w = delta_rule(x, y)

print("True weights:", true_w)

print("Learned weights:", w)What is DeltaNet?

DeltaNet

The parallel to the Delta Rule becomes clear when we break down the components:

- \(\beta_t \in \mathbb{R}\) acts as the learning rate

- \(\mathbf{k}_t \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is the input data

- \(\mathbf{v}_t \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is the target

- \(\mathbf{S}_{t-1} \mathbf{k}_t \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is our current prediction

We will revisit this form later, showing how it can emerge naturally from a single gradient descent step on a (online) loss function.

There’s another intuitive way to understand this update rule. Think of \(\mathbf{S}_{t-1}\mathbf{k}_t\) as retrieving the “old value” associated with the current key \(\mathbf{k}_t\) from memory. When we encounter a newly associated value \(\mathbf{v}_t\) for the same key, rather than blindly overwriting, we make a careful update:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{v}_t^{\text{new}} &= (1-\beta_t) \mathbf{v}_t^{\text{old}} + \beta_t \mathbf{v}_t, \\ \mathbf{S}_t &= \mathbf{S}_{t-1} - \underbrace{\mathbf{v}_t^{\text{old}} \mathbf{k}_t^\top}_{\text{erase}} + \underbrace{\mathbf{v}_t^{\text{new}} \mathbf{k}_t^\top}_{\text{write}} \end{align*}\]where \(\mathbf{v}_t^{\text{new}}\) is a learned combination of the old and current values, controlled by a dynamic \(\beta_t \in (0,1)\): when \(\beta_t=0\), the memory content remains intact, and when \(\beta_t=1\), we completely replace the old associated value with the new one.

DeltaNet as a Strong In-context Learning RNN

MQAR (Multi-Query Associative Recall)

The MQAR task works as follows: Each letter is associated with a number, and the model is asked to correctly recall the number associated with each letter in a query sequence.

For example, given the input:

A 4 B 3 C 6 F 1 E 2 → A ? C ? F ? E ? B ?

The format consists of:

- Key-Value pairs (before the arrow): Letters paired with their corresponding numbers

- Query sequence (after the arrow): Letters whose associated numbers need to be recalled

The correct output for this example would be:

4, 6, 1, 2, 3

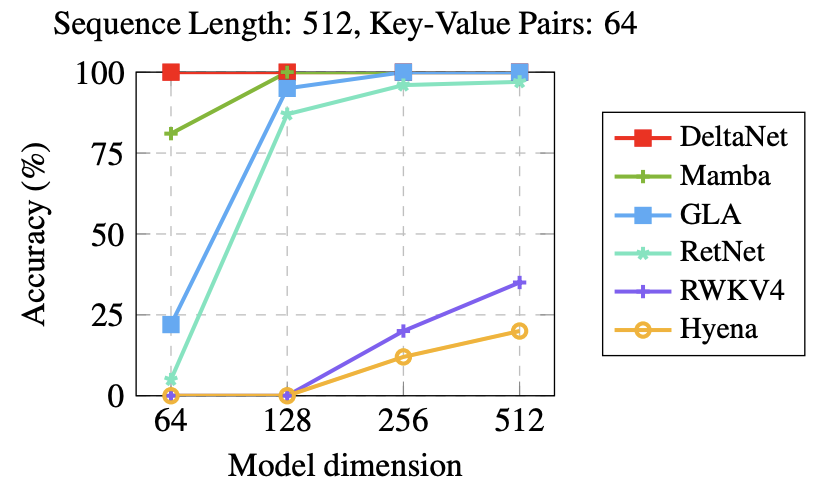

While conventional gated convolution and recurrent models generally underperform in this task, in our experiments, we show that DeltaNet

This initial success was particularly exciting—achieving perfect performance on MQAR exceeded our expectations. What makes this result especially promising is that MQAR performance strongly correlates with “Associative-Recall-Hit” in real-world language modeling tasks

We’ve also conducted experiments on MAD

| Model | Compress | Fuzzy Recall | In-Context Recall | Memorize | Noisy Recall | Selective Copy | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | 51.6 | 29.8 | 94.1 | 85.2 | 86.8 | 99.6 | 74.5 |

| Hyena | 45.2 | 7.9 | 81.7 | 89.5 | 78.8 | 93.1 | 66.0 |

| Multihead Hyena | 44.8 | 14.4 | 99.0 | 89.4 | 98.6 | 93.0 | 73.2 |

| Mamba | 52.7 | 6.7 | 90.4 | 89.5 | 90.1 | 86.3 | 69.3 |

| GLA | 38.8 | 6.9 | 80.8 | 63.3 | 81.6 | 88.6 | 60.0 |

| DeltaNet | 42.2 | 35.7 | 100 | 52.8 | 100 | 100 | 71.8 |

where DeltaNet demonstrates its strong in-context recall capacities. These synthetic tasks are inexpensive to run and offer clear evidence that DeltaNet is likely to perform well at scale. This motivated us to focus on developing DeltaNet’s training algorithm and kernel implementation—after all, scaling up an arbitrary architecture without demonstrating its potential would risk wasting significant time and resources.

In the next post, we’ll explore a beautiful algorithm that parallelizes DeltaNet across sequence length. But first, let’s build some intuition about why DeltaNet is particularly well-suited for in-context retrieval tasks.

Why is DeltaNet Superior at In-context Retrieval Compared to Linear Attention?

DeltaNet’s update rule can be derived by sequentially minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) between the desired output and the predicted output at each time step \(t\) using gradient descent:

Applying gradient descent to minimize this MSE loss gives:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{S}_t &= \mathbf{S}_{t-1} - \eta_t \nabla \mathcal{L}_t(\mathbf{S}_{t-1}) \\ &= \mathbf{S}_{t-1} - \eta_t \left(\mathbf{S}_{t-1} \mathbf{k}_t - \mathbf{v}_t\right) \mathbf{k}_t^\top \end{aligned}\]When the learning rate \(\eta_t\) is set to \(\beta_t\), this results in DeltaNet’s update rule.

In contrast, vanilla linear attention employs a linear loss function:

\[\mathcal{L}^\prime_t(\mathbf{S}) = -\langle \mathbf{S} \mathbf{k}_t, \mathbf{v}_t \rangle\]The corresponding update rule for linear attention is:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{S}_t &= \mathbf{S}_{t-1} - \eta_t \nabla \mathcal{L}_t^\prime(\mathbf{S}_{t-1}) \\ &= \mathbf{S}_{t-1} + \eta_t \mathbf{v}_t \mathbf{k}_t^\top \end{aligned}\]By setting \(\eta_t = 1\), the standard linear attention update is recovered.

Thus, DeltaNet’s superior performance in in-context retrieval becomes evident—it minimizes MSE at each step, making it ideal for tasks like associative recall where reducing large errors is crucial for accurate retrieval.